What to expect:

Obesity is globally recognised as a complex, relapsing, and chronic disease.1 Given its multifactorial nature, treating obesity requires an evidence-based management approach. Effective weight loss therapy aims to treat and prevent physical complications, whilst supporting patients’ mental well-being and tackling weight stigma.

This guide aims to help healthcare professionals explore the

efficacy and key limitations of the three main modalities of obesity

treatment. By learning about these treatments for obesity, medical

professionals may treat obesity with a comprehensive, holistic

management approach.

The principal goals in obesity management are to:

There are multiple guidelines available for obesity management,

which include recommendations on the three categories of intervention:

lifestyle therapy, pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery. Each

category can offer different levels of weight loss.3

Successful weight loss therapy has a number of health benefits:

● Prevention of obesity complications (e.g. cardiovascular diseases, high blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes)4: Weight loss can prevent a range of obesity-related complications. There is a linear correlation between weight loss and improvements in cardiovascular risk factors including blood pressure, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol.2 Through a successful and maintained weight loss of between 5-15% diabetes remission can occur in those who were recently diagnosed.2 Read more about the benefits of weight loss on health.

● Reduction of obesity-related health risks: Some of the complications experienced by patients with obesity can be due to excessive weight, including osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnoea, and asthma among others.2 Weight loss decreases the pressure on joints in those with osteoarthritis and the pressure on the airways in both asthma and obstructive sleep apnoea.

● Improvement in quality of life: A range of measures are used to assess quality of life in those with obesity including the DALY (disability-adjusted life years) measurement, which looks at the number of years of good health lost by a particular condition.4 In particular, maintaining weight loss been shown to cause marked improvement in quality of life measures.5

Cornerstone treatment of obesity: Lifestyle therapy

modifications are the cornerstone of all weight loss therapy and

should be the first-line intervention for all individuals.

Importantly, lifestyle modifications must be included as part of

any weight loss intervention.2

Body Mass Index (BMI) kg/m2: Lifestyle therapy

modifications for weight loss are recommended for all individuals

with a BMI ≥25 kg/m2.

In various studies, lifestyle modifications, including low-calorie diets, have shown to reduce weight by between 3-8%.6,7

Lifestyle changes encompass three main categories:

Diet modification is based on calorie reduction from dietary sources and causes patients to lose body weight through a calorie deficit.5 As the body uses fat stores in the liver and fatty tissues as fuel, rather than food, this causes a reduction in weight.

Increased exercise also contributes to calorie deficit as calories are used for physical movement.5 Regular bouts of aerobic exercise can also reduce blood pressure and hyperlipidaemia which are obesity-related risks.5 However, physical activity alone has been shown to have limited benefit in weight loss without calorie restriction.5 Therefore, a combination approach is best.

Behavioural change therapy works by setting realistic goals and self-monitoring. Counter-intuitively, this is a holistic approach which recognises that multiple factors outside of behaviour contribute to obesity, such as genetics and hormonal influences. That’s why behavioural therapy aims to set specific goals within a range that an individual can realistically reach.5 Regular self-monitoring has consistently been linked to both short and long-term weight loss and this is incorporated into behavioural therapy.5 Crucially, through cognitive restructuring, psychological triggers can be modified so that patients can overcome unhealthy eating habits.5

To learn more about diet difficulties, visit ‘Why don’t diets work?’.

For more guidance on Lifestyle Therapy Modifications, see page 91 of the AACE/ACE Guidelines (2016).

Pharmacological treatments of obesity utilise different mode of actions and across the different classes, they can provide 3-9% weight loss.12

Benefits of pharmacotherapy include:

Pharmacotherapy can be divided into non-prescription and prescription medications. Both are potential medical treatments for obesity but vary in efficacy.

Some diet supplements available without prescription claim to help with medical weight loss; however, there is little evidential basis to verify their use as weight loss treatments. In many countries, herbal products are classified under dietary supplements and therefore are not subject to regulatory testing and review, and therefore could be risky to health.

Prescription weight loss medications are only available following prescription by a qualified health professional.

Different prescribed weight loss medications contain different types of medication and can have differing effects. Studies have shown that taking prescription weight loss medications can result in between 3-9% weight loss.12 Other studies have shown that some individuals (6-20%) taking prescription weight loss medications in conjunction with lifestyle changes both lose 10% or more of their initial weight and maintain that initial weight loss.13 This highlights the role of pharmacotherapy in augmenting weight loss or preventing regain after initial weight loss through lifestyle interventions.13

Anti-obesity medications can act directly on the central nervous system, inducing weight loss by reducing appetite, or act peripherally and induce weight loss by interfering with fat absorption from the gastrointestinal tract.14

Medications cannot replace key lifestyle factors such as regular physical activity or healthy eating habits. Prescription medications in conjunction to a lifestyle program have shown clinically meaningful weight loss results, thus a combination approach is recommended.13 It is also important to consider the side effects of prescription medications and a risk-benefit analysis should be performed prior to prescription. Delivering the best treatment for obesity should always be holistic and consider the patient’s needs.

For more guidance on Pharmacological Treatment Options, see page 102 of the AACE/ACE Guidelines (2016).

There are a number of different types of weight loss surgery, with each option providing different weight loss efficacies ranging between 7-38%.16,17 This efficacy means that bariatric surgery can be a highly effective method of weight loss for patients who are overweight or living with obesity.

One study showed that rebound weight gain can occur in up to 50% of people, two years following surgery.18 The percentage of weight regain varied amongst individuals and depending on the type of bariatric surgery, studies have shown a mean weight regain of between 8-23.4% of the initial weight loss.18, 19 Although there can be rebound weight gain, overall weight loss through bariatric surgery remains high compared to non-surgical weight loss treatments.3,15 This makes bariatric surgery an effective treatment for weight loss.

The most common types of weight loss surgery are:

Weight loss surgery can be invasive and there is a risk of postoperative complications.15 These risks vary depending on the surgery type.15 Typical surgical complications include bleeding, herniation, peritonitis, deep vein thrombosis and post-operative vitamin malabsorption among others.15,21 Some of these complications can be more serious than others but overall, peri-operative mortality is low and occurs in less than 1%.21

For more guidance on Bariatric Surgery, see page 131 of the AACE/ACE Guidelines (2016).

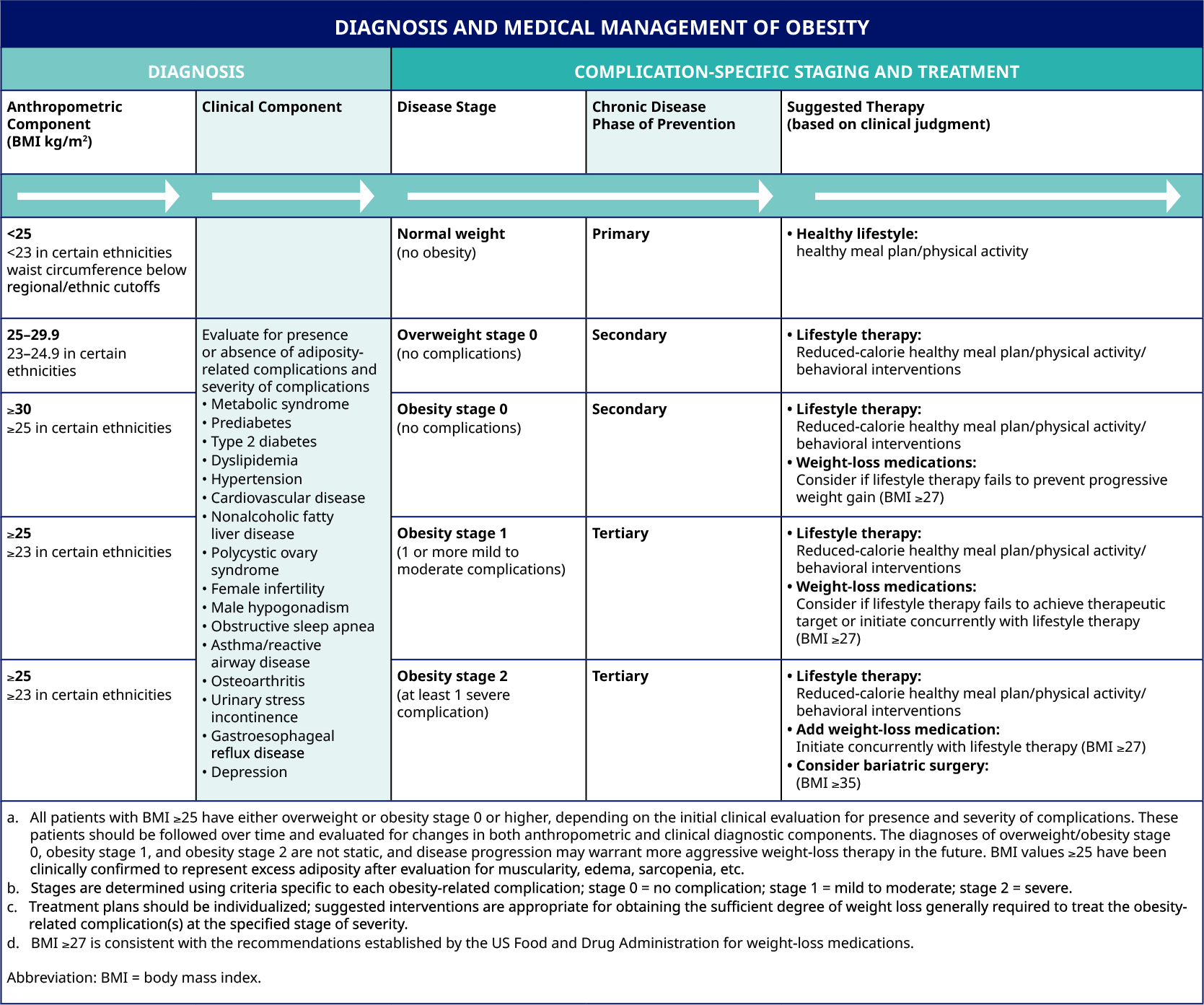

Below, you can also find a practical overview of the appropriate suggested obesity therapy, based on your diagnosis and complication-specific staging.

You can download practical step-by-step guides for the treatment of both obesity in adults and in children by clicking the Download button.

If you found these resources valuable, click on the envelope icon above to share them with your colleagues, and support other medical professionals in their daily practice.

1. Caterson I.D., Alfadda A.A., Auerbach P. et al. Gaps to bridge: Misalignment between perception, reality and actions in obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019; 21:1914-1924.

2. Durrer Schutz D., Busetto L., Dicker D., et al. European Practical and Patient-Centred Guidelines for Adult Obesity Management in Primary Care. Obes Facts. 2019;12:40–66.

3. Garvey W.T., Mechanick J.I., Brett E.M., et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines for Medical Care of Patients with Obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(Suppl 3):1–203.

4. Yumuk V., Tsigos C., Fried M., et al. European Guidelines for Obesity Management in Adults. Obesity Facts. 2015;8:402–424.

5. Wadden T., Webb V., Moran C., Bailer B. Lifestyle Modification for Obesity. Circulation. 2012;125(9):1157-1170.

6. Johns D., Hartmann-Boyce J., Jebb S.A., et al. Diet or Exercise Interventions vs. Combined Behavioral Weight Management Programs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Direct Comparisons. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:1557–1568.

7. Wharton S, Lau D, Vallis M, Sharma A, Biertho L, Campbell-Scherer D et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2020;192(31):E875-E891.

8. Mann T., Tomiyama A.J., Westling E., et al. Medicare's search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. Am Psychol. 2007;62:220–233.

9. Jensen M.D., Ryan D.H., Apovian C.M., et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102–138.

10. Rye P., Modi R., Cawsey S., et al. Efficacy of high-dose liraglutide as an adjunct for weight loss in patients with prior bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2018;28:3553–3558.

11. Busetto L., Dicker D., Azran C., et al. Practical Recommendations of the Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the Study of Obesity for the Post-Bariatric Surgery Medical Management. Obesity Facts. 2017;10:597–632.

12. Kushner R. Weight Loss Strategies for Treatment of Obesity: Lifestyle Management and Pharmacotherapy. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;61:246–252.

13. Yanovski S., Yanovski J. Long-term Drug Treatment for Obesity. JAMA. 2014;311(1):74.

14. Li M. and Cheung B.M. Pharmacotherapy for obesity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:804–810.

15. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) website. Bariatric surgery procedures. Available at: https://asmbs.org/patients/bariatric-surgery-procedures. Last accessed: May 2021.

16. Courcoulas A., Christian N., Belle S., et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA. 2013;310:2416–25.

17. Berry M., Urrutia, Lamoza P., et al. Sleeve Gastrectomy Outcomes in Patients with BMI Between 30 and 35–3 Years of Follow-Up. Obes Surg. 2018;28:649–55.

18. Magro D., Geloneze B., Delfini R., Pareja B., Callejas F., Pareja J. Long-term Weight Regain after Gastric Bypass: A 5-year Prospective Study. Obesity Surgery. 2008;18(6):648-651.

19. Cooper T., Simmons E., Webb K., Burns J., Kushner R. Trends in Weight Regain Following Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) Bariatric Surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2015;25(8):1474-1481.

20. Wolfe B., Kvach E., Eckel R. Treatment of Obesity. Circulation Research. 2016;118(11):1844-1855.

21. Kassir R., Debs T., Blanc P., et al. Complications of bariatric surgery: Presentation and emergency management. International Journal of Surgery. 2016;27:77-81.

HQ21OB00066, Approval date: October 2021

The site you are entering is not the property of, nor managed by, Novo Nordisk. Novo Nordisk assumes no responsibility for the content of sites not managed by Novo Nordisk. Furthermore, Novo Nordisk is not responsible for, nor does it have control over, the privacy policies of these sites.

At Novo Nordisk we want to provide Healthcare Professionals (HCPs) with scientific information, resources and tools.