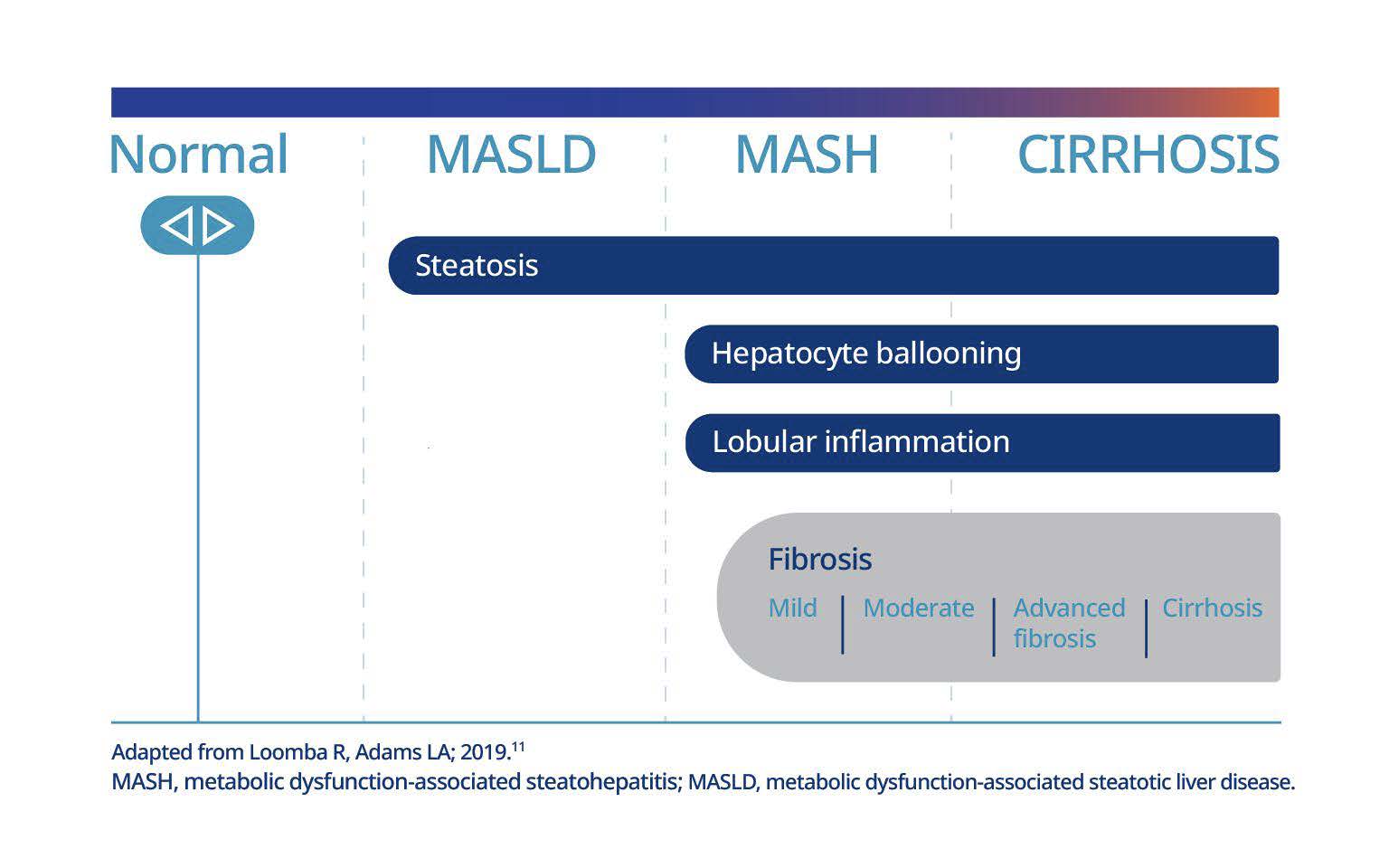

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is a chronic, progressive condition of the liver characterised by worsening liver fibrosis and steatohepatitis, a type of fatty liver disease, which can have life-threatening consequences.1 The condition has a high prevalence in people with overweight and obesity – yet it can often remain undiagnosed.2-7

Direct quote from a person living with MASH

NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

For people living with MASH, obesity significantly increases the risk of further liver health deterioration, as well as impacting physical and mental well-being and quality of life. 3,10

If left untreated, MASH can progress from no fibrosis (F0) to advanced fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis (F4) in just under 6 years for some patients. 11‡

MASH is closely linked with obesity, as well as other obesity-related complications, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD)4-7

Adapted from Younossi Z, et al; 2022.10

When MASH remains undiagnosed, the risks of worsening outcomes and complications increase.8

The image shown is a model and not a real patient.

International guidelines recommend early screening of at-risk patients § so that MASH can be identified and tackled promptly to prevent further liver damage and associated complications.6,18

Comprehensive MASH care for your patients should include weight management with evidencebased therapies 19,20

Proportion based on the published prevalence of MASH in adults across France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK in 2018, which ranged from 11.9% to 12.7% for diagnosed MASH and from 87.3% to 88.2% for undiagnosed MASH.8

†NAFLD is the former nomenclature for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). MASH is the revised terminology for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which better represents the condition’s aetiology.

‡ Fibrosis staging ranges from F0 to F4, with clinically significant fibrosis starting at F2 (moderate fibrosis). Early-stage MASH is F0 or F1 (mild fibrosis), advanced MASH is F3 (advanced fibrosis), and cirrhosis is F4.21,22

§Includes guidelines from the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)–European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD)–European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).6,18

HQ25OB00133 | Approved August 2025

The site you are entering is not the property of, nor managed by, Novo Nordisk. Novo Nordisk assumes no responsibility for the content of sites not managed by Novo Nordisk. Furthermore, Novo Nordisk is not responsible for, nor does it have control over, the privacy policies of these sites.

At Novo Nordisk we want to provide Healthcare Professionals (HCPs) with scientific information, resources and tools.